The Lean Enterprise Institute’s Lean Transformation Framework encompasses five questions. The first question is: “What problem are we trying to solve?” For most people, it is a reasonable first question to ask. But there are two other important related questions: 1. Who should answer that first question? and 2. Is there a common answer? In LEIs Lean Transformation Framework, it seems that everyone should answer that first question and that there is no common answer for organizations. The question is open-ended and so too will be the answer depending on who answers it; anyone from CEO to shop floor associate.

For this reason, LEIs Lean Transformation Framework seems to me more likely to generate large amounts of Lean “busywork” than produce major business results. Allow me to explain this iconoclastic point of view:

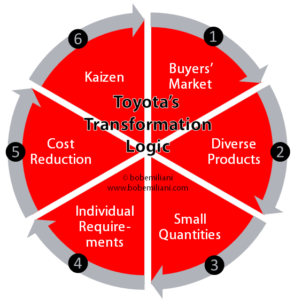

The context, Lean transformation, reflects changes in mindset and practices across an entire organization. Given the scope of change, the first question can only be answered by the executive team. After all, Lean, we are now told, is a strategy, and so executives are clearly responsible for answering this first question for an organization. Given what concerns CEOs, the answer will surely be specific and connected to actual business needs. One such need that all businesses have, and which all CEOs care about, is cost reduction. So, the question “What problem are we trying to solve?” can yield a common answer both within a business or for any business: cost reduction. There are many methods to achieve cost reduction. However, executives should seek methods that strengthen competitiveness, not weaken it. Strengthening competitiveness means finding methods to reduce costs when production volumes are low. Simply increasing production quantities to reduce costs (i.e. economies of scale), which anyone can do, weakens competitiveness in buyers’ markets.

While the first question must cascade through the organization, so too must its answer in order to focus team and individual problem-solving efforts. If not, then people will be busy solving problems for which there is no actual business need. This is called “busy work,” which we have all experienced. If employees continue the same old pattern of doing “busy work” while under LEI’s Lean Transformation Framework, then people will work to solve problems that have no business need and produce no business result. And there will be no Lean transformation.

Most businesses operate in competitive (buyers’) markets. Daily competition and the existence of other threats to survival means a business cannot afford to solve problems disconnected from actual needs and which have no business impact. It wastes time and resources, and will put them further and further behind the competition as time goes by. It also wastes people’s (employees’) lives.

For Taiichi Ohno, the answer to the question “What problem are we trying to solve?” was not ambiguous or open-ended. It was specific and reflected actual needs as perceived by Toyota’s top leaders in their struggle to compete against Ford and General Motors’ products in Japan, their competitors’ cost-reduction efforts, customers’ never-ending desire to pay less for improved products over time, the need to generate profits, and survival. In his book, Toyota Production System, Ohno clearly articulated the specific problem he was trying to solve:

“Our problem was how to cut costs* while producing small numbers of many types of cars.” (p. 1)

What was the business need? The business need was the changing market that Toyota faced:

“… [a] marketplace [that] required the production of small quantities of many varieties under conditions of low demand…” (p. xiii)

This, in turn, required the creation of a production system responsive to Japan’s market conditions (buyers’ market) so that Toyota could:

“…make products that differ according to individual requirements…” (p. xiv)

Toyota’s transformation was the change from batch-and-queue production to flow, to satisfy customers. And, of course, the transformation affected all other parts of the business as well. That is why Ohno said:

“…[it] means nothing less than adopting the Toyota production system as the management system of the whole company.” (p. 41)

LEIs Lean Transformation Framework says that you should take a “situational approach.” It says every situation unique and every countermeasure unique. It that true? In reality, your business environment, your problem, and your customers’ desires are the same as what Toyota faced in the late 1940s and still faces in 2017. Therefore, you need to figure out how to reduce costs while producing small numbers of many types of products. How will you do that? You must change from batch-and-queue to flow, and transform all other parts of the business to support that. A situational approach? For most businesses, that is nonsense.

But it is not just changes in processes throughout the company. It is also changes in mindset for both management and workers. The change in mindset – what Ohno called “a revolution in consciousness” (p. 14) – is especially difficult for managers because it encompasses numerous economic, social, political, and historical factors that serve as powerful bulwarks against changes in thinking (as well as recognizing simple realities such as buyers’ markets). This is why most Lean transformations fail, notwithstanding the ubiquity of Lean “busy work” and the lack of business results.

The change in manager’s mindset has proven to be the greatest challenge over the course of the 125-year history of progressive management. For example, when Ohno said “cut costs,” the conventional-mindset manager, whether in 1917 or 2017, immediately jumps to the idea of reducing headcount through layoffs. Hence, people today widely associate Lean with layoffs. But, Ohno never meant layoffs. He meant cutting costs in ways that did not harm people. In fact, he wanted people to benefit from the challenge and experience of participating in cost-cutting. How? By developing human capabilities; using their creativity and resourcefulness through hands-on and brain-on engagement in what he called “rationalization.” What Ohno meant by “rationalization” was “kaizen” – Toyota’s industrial engineering-based kaizen methods – to improve processes and the work, thereby improving productivity and cutting costs, while simultaneously satisfying customers and generating profit. This is why Taiichi Ohno stressed “the equally important respect for humanity” (p. xiii) in efforts to create and sustain the transformation.

Ohno said:

“I wanted to illustrate how it [TPS] reduces costs by improving productivity with human effort and innovation [kaizen] even in periods of severe low growth – not by increasing quantities.” (p. 119)

For every business that operates in a competitive environment – which is most businesses, whether for-profit or not-for-profit – the problem you are trying to solve today is virtually the same problem that Ohno and his team worked to solve over a 30-year period beginning in 1947. The situation is the same. The countermeasure is the same. And the process is the same.

“The Toyota production system, however, is not just a production system. I am confident it will reveal its strength as a management system adapted to today’s era of global markets…” (p. xv)

But, given that there are large differences between Lean transformation and Toyota transformation, you must make a choice: Lean transformation (ambiguous and open-ended, devoid of kaizen and other important umami), or Toyota transformation. Choose the formhttps://bobemiliani.com/kaizen-forever/er and you will increase the risk of losing ground to competitors. Choose the latter and not only will you work towards solving Ohno’s problem, you will instill organizational commitment and discipline to customer satisfaction.

* If you rely solely on budgets and spreadsheets as your indicators of costs, then you will never understand TPS. When Ohno says “costs,” he is referring to anything that directly or indirectly creates or reduces cost, whether it is measurable or not, and whether it is visible or not. So, “costs” means: productivity, hiring, training, work, work signals, work standards, work sequence, machines, tooling, maintenance, queue time, set-up time, part-travel time, cycle time, lead-time, space, materials, consumables, inventories, taxes, warehouses, energy, abnormal conditions, demand, parts, waste, unevenness, unreasonableness, spirit, challenge, creativity, innovation, teamwork, learning, evolution… and a thousand more things.